SEE THE STORY BEHIND THIS PICTURE FOR FREE!

JOIN US

Become an Alabama Pioneers Patron – FREE

Hightstown, New Jersey – Garment Plant faces difficulties

“By December the $60,000 contributed by the 120 approved homesteaders of Hightstown Homestead in New Jersey was exhausted, and orders for coats had not been large enough for a profit. Brown, who led a delegation of homesteaders to Washington, accused the government of a breach of faith in not having completed the house construction as scheduled, thus preventing the success of the factory.”1

(Air view of Hitghtstown Homestead in 1936)

“Although the Resettlement Administration felt that the failure of the factory was due to poor management, it was keenly embarrassed by the lags in construction. This was particularly true of the Family Selection Section, which had readied the homesteaders for moving without knowing of the delay by the Construction Division. Several homesteaders faced acute hardship as a result. Therefore the Resettlement Administration granted Brown a loan of $50,000 for the further operation of the factory.”2

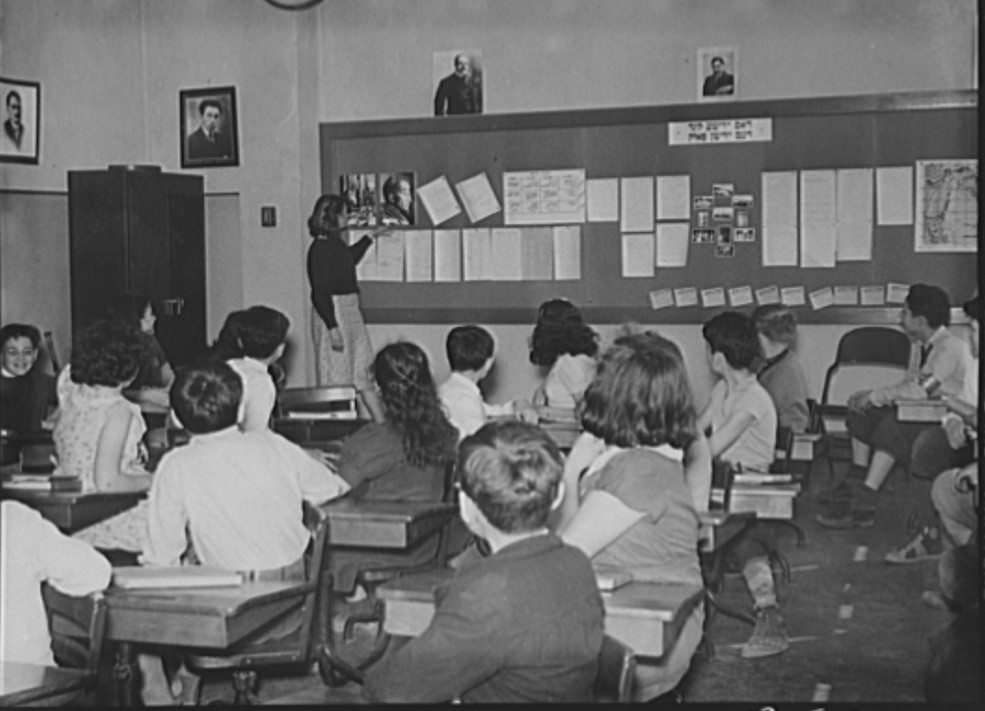

(Director of Information Hightstown, New Jersey

speaking to visitors in 1936)

(Samuel J. Finkler and his assistant Harry Glanz were in charge of family selection – Nov. 1936)

“The second factory season opened in January, 1937. Since the Resettlement Administration had completed the homes, any further losses could not be attributed to a lack of ready labor, although Brown could claim that the non-fulfillment of orders the first year had permanently ruined the market for the factory’s products. The second factory season ended by Easter, with no further operating funds.”3

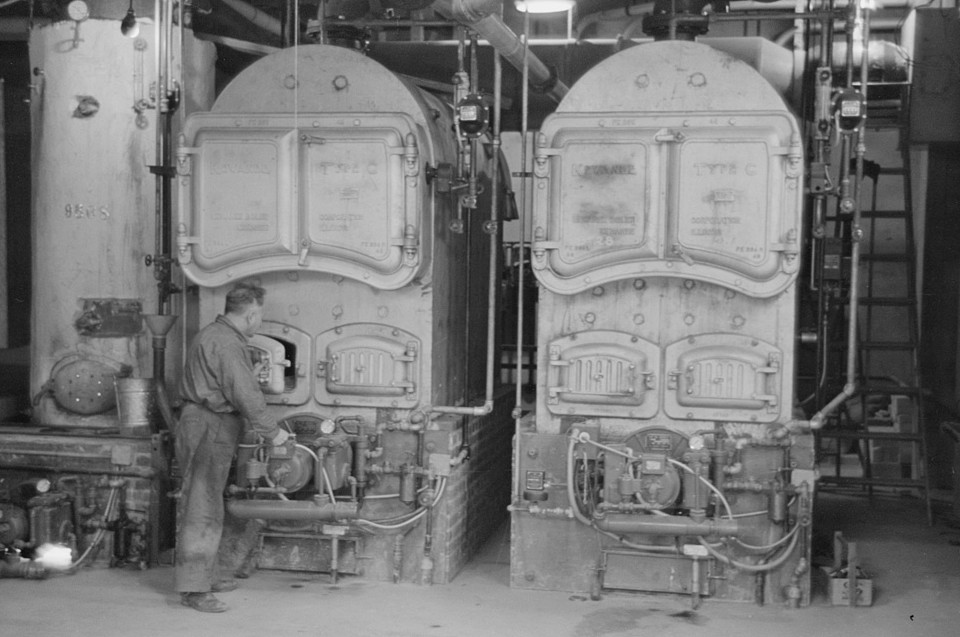

(Boilers provided to heat the garment factory at Jersey Homesteads, Hightstown, New Jersey 1936 photo by Russell Lee)

(Boris Drasin, president of the workers’ Aim Association Inc., works as an operator in the garment factory at a the same wage as the other operators. Nov. 1936 by Russell Lee)

(Children coming home from school. Hightstown, New Jersey Dec. 1936 photo by Arthur Rothstein)

(Closeup of cloak operators in cooperative garment factory at Jersey Homesteads, Hightstown, New Jersey 1936 Photo by Russell Lee)

(Closeup of cutter’s hands (cutting cloth), Jersey Homesteads, Hightstown, New Jersey 1936 photo byRussell Lee)

(Closeup of man working sewing machine in garment factory, Jersey Homesteads, Hightstown, New Jersey 1936 photo by Russell Lee)

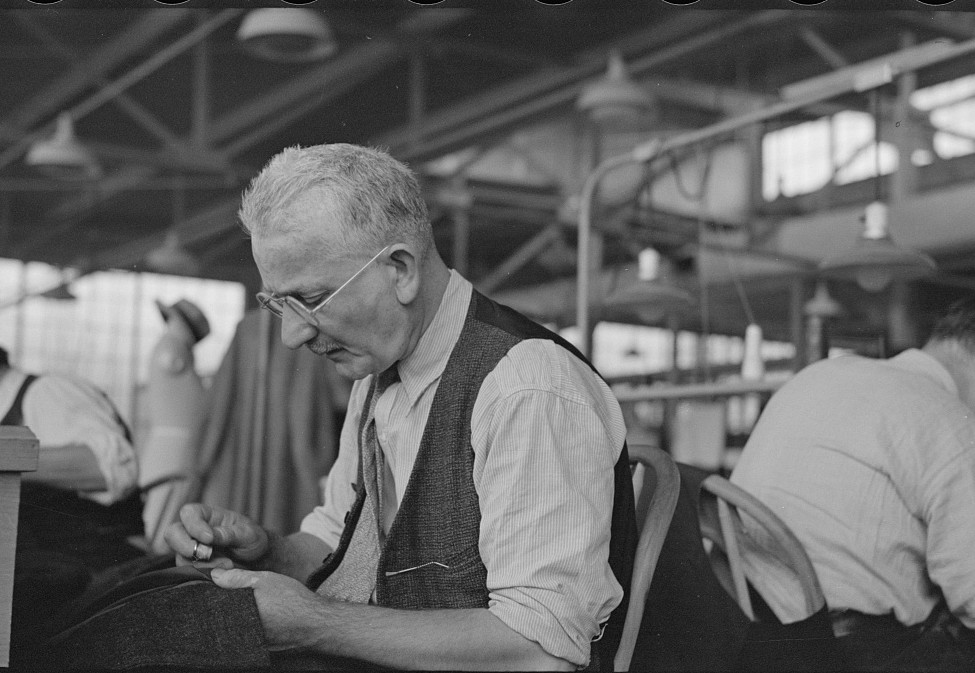

(Closeup of tailor in garment factory, Jersey Homesteads, Hightstown, New Jersey 1936 photo by Russell Lee)

(Closeup of tailor, Jersey Homesteads garment factory, Hightstown, New Jerseyphoto by Russell Lee)

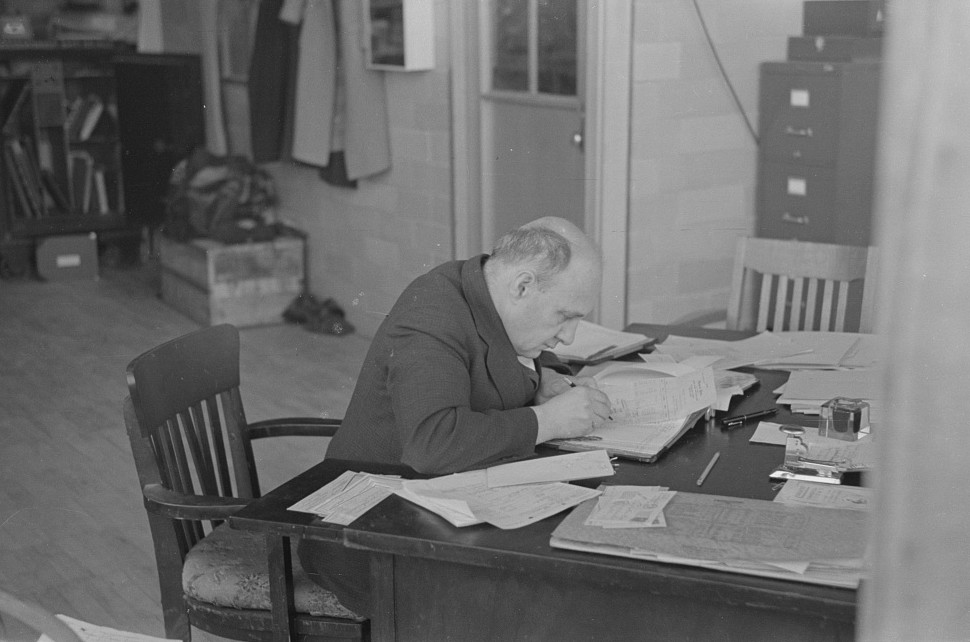

(Comptroller of factory at Jersey Homesteads at work in office, Hightstown, New Jersey 1936 Photo by Russell Lee)

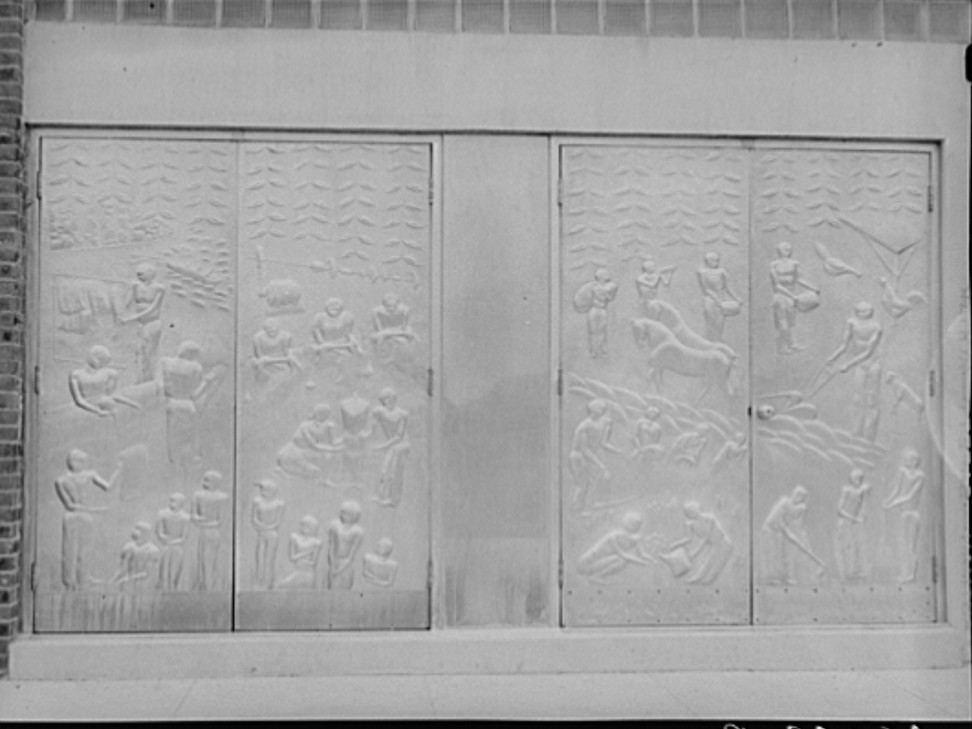

(Below are Doors to community center at Jersey Homesteads at Hightstown, New Jersey 1936 Arthur Rothstein 1938)

(Eugene Isaacs, tailor at Hightstown Garment factory photo by Russell Lee Nov. 1936)

(Garment worker at Hightstown factory, New Jersey Nov. 1936 photo by Russell Lee)

(Garments manufactured by residents of Jersey Homesteads, Hightstown, New Jerseyphoto by Russell Lee Nov. 1936)

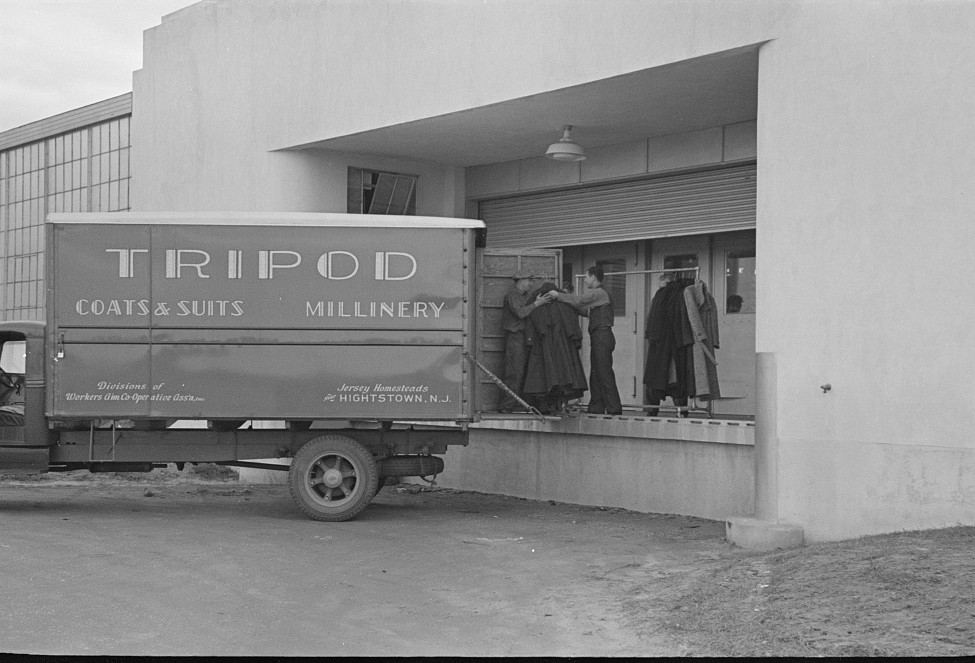

“Brown’s appeal for a new loan from the Resettlement Administration (now part of the Department of Agriculture) was rejected. Brown accused the government of bad faith and raised $50,000 himself, forming the Tripod Coat and Suit, Incorporated, to design, promote, and distribute the garments. The factory products were to be sold through farm co-operative outlets throughout the country.”4

(Half-made garments on the racks at Hightstown garment factory Nov. 1936 photo by Russell Lee)

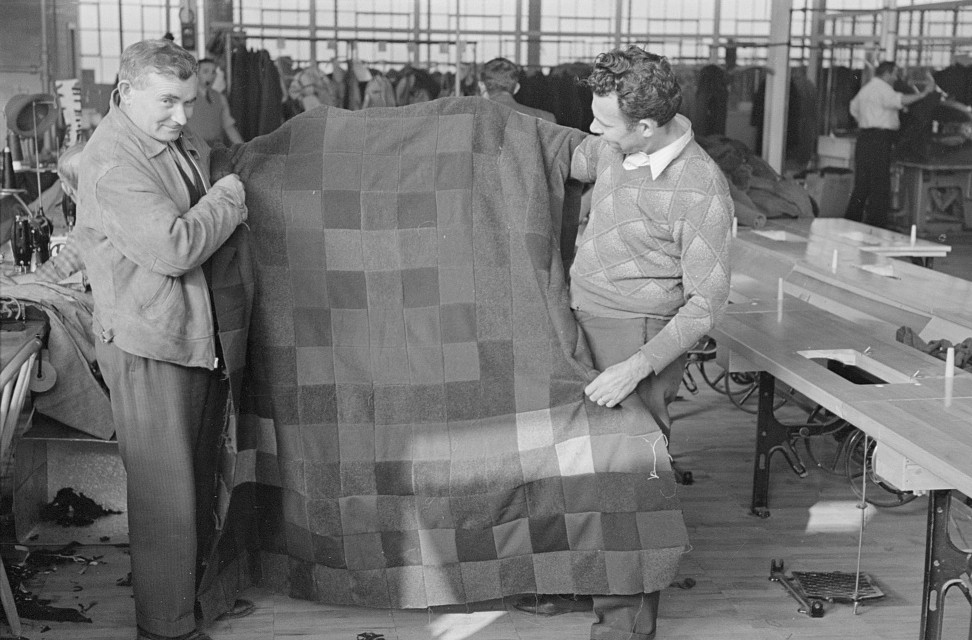

(Harry Kaplan (rt) showing blanket he made from waste cloths Nov. 1936 photo by Russell Lee)

(Hat makers at the cooperative garment factory, Hightstown, New Jersey Nov. 1936 photo by Russell Lee)

(Homesteaders’ daughters are employed in the millinery department of the cooperative garment factory at Jersey Homesteads, Hightstown, New Jersey Nov. 1936 Russell Lee)

“The Tripod products were distributed by seven trucks, each of which carried complete lines of coats, plus racks and mirrors. One truck reported sales of $1,000 in one day. But by May, 1938, Tripod suspended operations for lack of funds. Appealing to the Farm Security Administration, Brown finally received a loan of $150,000, with stipulations intended to prevent reckless expenditures or overproduction.”>5

(The factory has its own truck, which makes deliveries to its two rooms in New York, Jersey Homesteads nov. 1936 photo by Russell Lee)

“Almost unbelievably, these funds were exhausted in less than a year. The Farm Security Administration had to admit the complete failure of the co-operative factory and adamantly refused to grant Brown any further aid.”6

“Long before the final failure of the factory in April, 1939, the housing shortage at Jersey Homesteads had become a housing surplus. Even though the 200 homes were completed, the Resettlement Administration was unwilling to move more families into the colony than the economic opportunities warranted. In addition, no tenants could be found who were willing to contribute $500 to a factory that was an obvious failure.”7

“In February, 1938, ninety-six homes were vacant, with the Resettlement Administration threatening to lease them to nonparticipating tenants, and this it later did. Jersey Homesteads never contained more than 120 participating Jewish families.

The Jersey Homesteads agricultural association was organized in the summer of 1936, with ninety-seven homesteaders joining. The farm co-operative had $16,000 profit from the New Jersey Rural Rehabilitation Corporation, which had leased the farm land for the first year, and two loans from the Resettlement Administration totaling $133,692.8

(Truck driver at the Hightstown, New Jersey, project Nov. 1935 photo by Carl Mydans)

“The general farm of 412 acres was operated by seven experienced farmers who had been selected as homesteaders for that purpose. They received a regular salary of twenty-five dollars a week from the agricultural association. By raising truck crops for the market, the farm made a profit of $17,000 in 1936, only to lose money consistently in the following years. In the spring of 1937 a poultry unit was started, and a nearby dairy farm was purchased in the fall of 1937.

(Scene at the New Jersey Homesteads cooperative. Near Hightstown, New Jersey Dec. 1936 Photo by Arthur Rothstein)

Contrary to Brown’s expectations, the three farm units never provided employment for more than thirteen people on the project, and these were the professional farmers. The factory workers, used to indoor work and union wages, were not willing to supplement their earnings by farm work, even in periods of unemployment. As a result transient Negro laborers were employed in busy seasons. Of the three units, only the poultry plant managed to make any profits. After lasting only a year and losing $15,000, the dairy farm was leased to an outside co-operative.

(House at Jersey homestead 1937 photo by Arthur Rothstein)

The third leg of the co-operative tripod, the consumer outlets, was slightly stronger than the factory and farms. The clothing store was doomed with the factory, but the grocery and meat market had periods of limited prosperity, while the small tearoom managed to survive, albeit with inadequate stock and facilities.

The three co-operatives at Jersey Homesteads were each controlled by a Board of Directors elected by the members. Each of the co-operatives was represented in a community council, which approved all new members admitted to the community. Each member of the co-operatives had one vote and was to share equally in any dividends. The homesteaders entered into the co-operatives with great enthusiasm, making co-operation almost a religion. They even formed a co-operative political party, which elected their first mayor. Yet enthusiasm was not enough.

The co-operative factory lost money because of an inexperienced manager, because of production in excess of orders, because of an overly ambitious line of goods, and because of high labor costs and inefficient production. Even though many of the homesteaders felt that the failure was the fault of the government, they would have been more realistic if they had placed the blame on themselves and their own attitudes. Habituated to highly competitive endeavor, they were frankly seeking more wages and a better job for themselves rather than a new way of life. Co-operation meant benefits to the exclusion of sacrifices. Thus, in the case of the farm units, the homesteaders, except for the farmers, were primarily interested in what they could get from the farms. They wanted lowered prices for farm products but were unwilling to work for the lower farm wages. Eventually the nonfarmers in the agricultural association secured control of the Board of Directors and tried to run the farms for their own benefit. Even the homesteaders’ cohesiveness sometimes hindered, for their attitude was one of “you protect me and I will protect you.” Thus inefficient workers were retained. A clerk in the co-operative store, when dismissed, picketed the store the next day, and not a customer passed him. He was rehired, since all business had ceased.

Start researching your family genealogy research in minutes for FREE! This Ebook has simple instructions on where to start. Download WHERE DO I START? Hints and Tips for Beginning Genealogists with On-line resourcesto your computer immediately

Reviews

“This book was very informative and at a very modest price. One web site I may have missed in your book that has been very helpful to me is genealogybank.com. I found articles about several of my ancestors in their newspaper archives. Thank you for your great newsletter and this book.

“The book was clear & concise, with excellent information for beginners. As an experienced genealogist, I enjoyed the chapter with lists of interview questions. I’d recommend this book to those who are just beginning to work on their genealogies. For more experienced genealogists, it provides a nice refresher.”