On a cloudless sunny morning with a comfortable breeze blowing from the south, an event took place that changed the barren land of Oklahoma forever.

On April 22, 1889, thousands of potential settlers from all over the world lined up to participate in the Oklahoma land rush.

The rushers massed along the line by 9:00 am and at precisely noon, a captain from the Fifth Cavalry gave the signal and the bugler blew reveille. The Oklahoma Land Rush had begun. The ground shook as thousands of horses and wagons raced forward in search of their American dream.

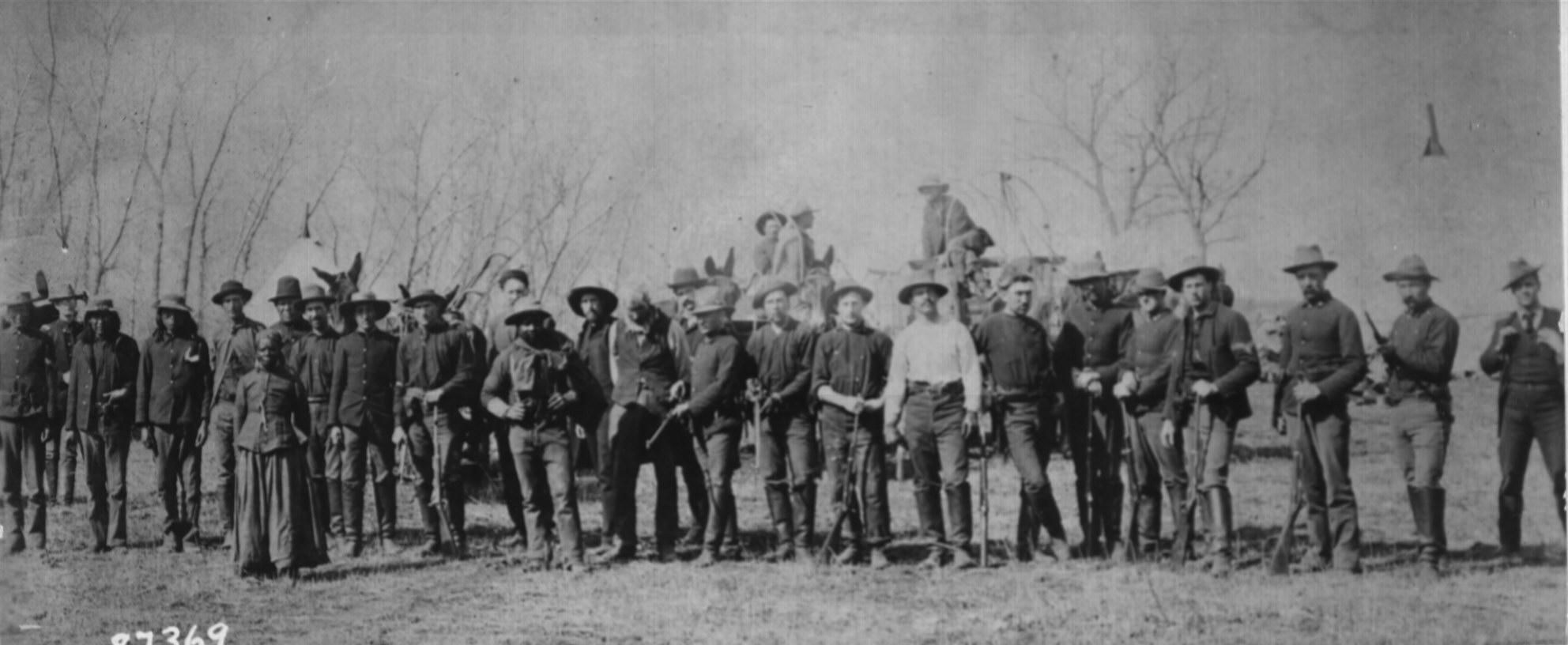

Troop`C,’ 5th Cavalry, which arrested boomers and squatters prior to opening of Oklahoma, ca. 1888 (National Archives)

The history behind the land rush

In 1862, at the height of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act into law. The law was intended to open western lands to settlement by allowing those filing a claim to settle on up to 160 acres of unappropriated federal land for five years.

RIBBON OF LOVE: 2nd edition – A Novel Of Colonial America: Book one in the Tapestry of Love Series

Over that period, the claimant had to improve the land and cultivate a certain percentage of it for agriculture. If such improvements were made, the land would belong to the claimant at the end of the five years. The Homestead Act was very successful in encouraging people to move west.

Native Americans were in Oklahoma

However, there was a problem in the new territory of Oklahoma. In the 1820s and 30s, the United States had forcibly relocated the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaaw, Creek, and Native Americans to move to Oklahoma and after their arrival, the government claimed the land would be theirs “for as long as the stars shall shine and the rivers may flow.”

When the Homestead Act was passed, the Five Civilized Tribes found themselves besieged on all sides by people who wanted their land. Over the next two decades, much pressure was brought to bear on Congress to once again forcibly remove the Five Tribes and open their reservation lands to homesteading and settlement.

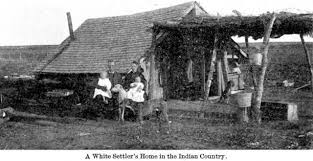

Dawes Severality Act gave each 160 acres

In 1887 the government passed the Dawes Severality Act. This law, which was thought to be a “Homestead Act” for Indians, divided existing tribal and reservation areas into 160 acre plots, one plot for each head of household. The law was meant to hasten the “civilizing” process of Native Americans, but in reality amounted to a reduction in tribal lands. After 160 acres of land was allotted to each Indian head of household, there were still thousands of acres of land left over and the land was open to white settlers.

At the same time, an influx of other Native American tribes had been relocated to Oklahoma so the five tribes were convinced to cede roughly one half (the western portion) of their lands to new Native American tribes.

Unassigned land was sold

Before all these “unassigned lands” were filled, the Creeks and Seminoles were also convinced to sell an additional 1,887,796 acres to the United States. On March 2, 1889, the U.S. Congress passed the annual Indian Appropriations Bill that opened this 1.9 million acre portion of the “unassigned lands” in Oklahoma and newly-inaugurated President Benjamin Harrison signed the bill on March 23.

Historic land rush

President Harrison opened the approximately 1.9 million acres to white settlement. As a means of quickly distributing the land to white settlers, he designated the first historic land rush.

At noon on April 22, 1889, the future setters would literally be in a race to claim free land, first come, first served. In an unprecedented move, under the provisions of the Homestead Act, single women and widows could be homesteaders the same as men. It is estimated that several hundred women made the 1889 land rush.

Sooners were removed

Prior to that date, President Harrison sent two regiments of U. S. cavalry troops into the area to clear the land of squatters and ensure no one entered early. The troops also surveyed the land and divided it into 160-acre tracts marked with cornerstones. Anyone who crossed into the lands prior to noon on the appointed day would forfeit his or her right to homestead in Oklahoma. Those that tried anyway were called “sooners.”

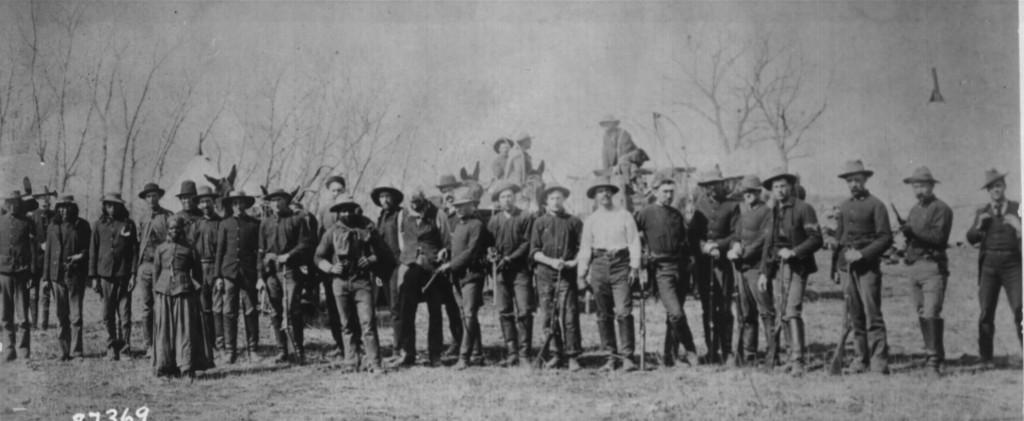

A white settler house in Indian Country

Prospective settlers crowded on the 300-mile perimeter of the Indian lands during the month of March, 1889. Lawlessness prevailed in the small border towns that sprang up overnight as they waited for the appointed day. A popular refrain that symbolized the lawlessness of the border towns was “160 acres or six feet, and I don’t give a damn which.”

The land rush began

“At precisely noon, a captain from the Fifth Cavalry gave the signal and the bugler blew reveille. The Oklahoma Land Rush had begun.”

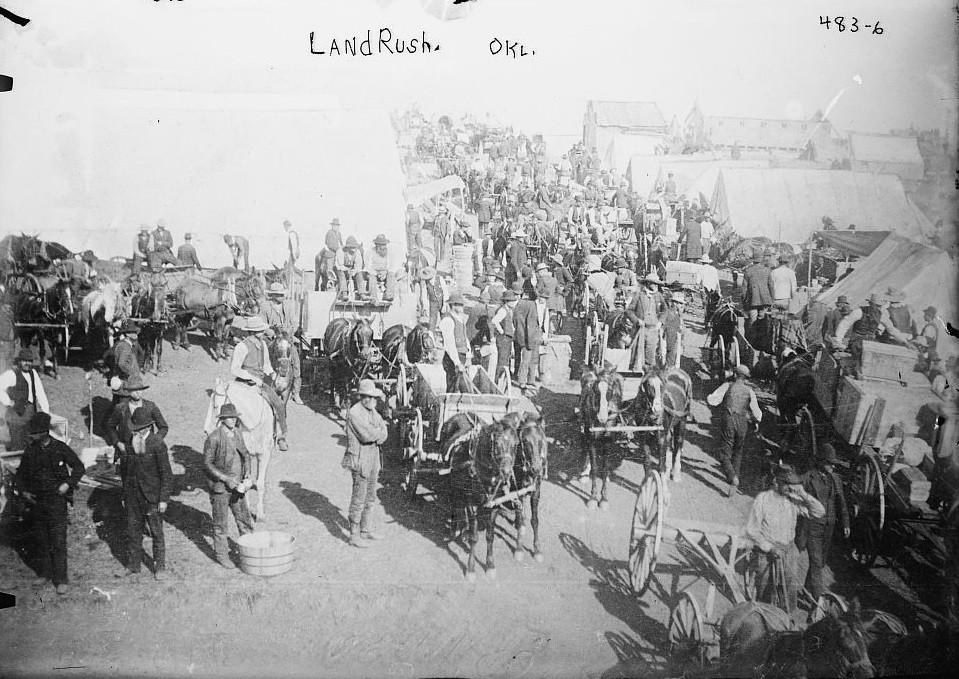

Oklahoma land rush by Bain News Service

Not all who wanted land had a horse or wagon so the government even ordered trains to be available for prospective settlers to ride. The trains traveled 15 miles per hours, the approximate speed of the average horse.

“Noise, dust, and confusion abounded as approximately 50,000 men, women, and children rushed for only 12,000 available tracts of land. Hammers pounded stakes into the ground; wagons clattered along; tents and shelters went up as quickly as possible. Claim jumpers and legitimate settlers argued and cursed one another, and shots were fired on more than one occasion.”

One reporter wrote of the event, “…the people went out like flies out of a sugar cask, and in five minutes a square mile of the prairie was spotted with squatters looking like flies on a sticky paper…we passed populous towns, built in an hour…we had seen the sight of the century.”

Holding down a lot by photographer C. P. Rich

“It soon became obvious that sooners had much more success infiltrating Oklahoma prior to the official beginning of the land rush than most had expected. Two hopeful settlers on fast horses were quite surprised to come upon one old man who had already plowed a field and had four-inch garden onions rising from it. The old man explained that he was no sooner; he simply had the fastest team of oxen in the world, and the Oklahoma soil was so rich that his onions had grown that high in just 15 minutes.”

Towns were built overnight

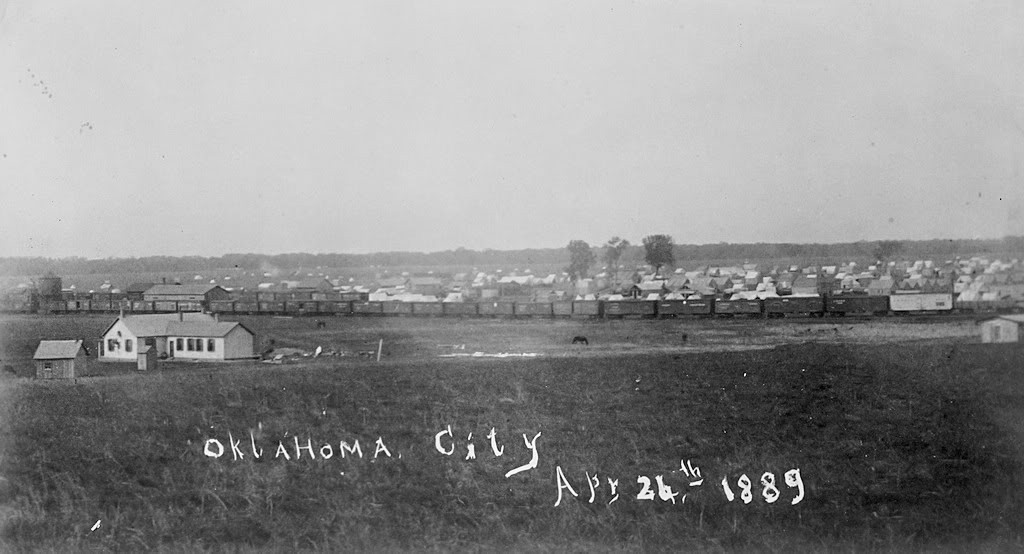

By late afternoon, thousands of people were milling around in Guthrie, Oklahoma City, and other new towns.

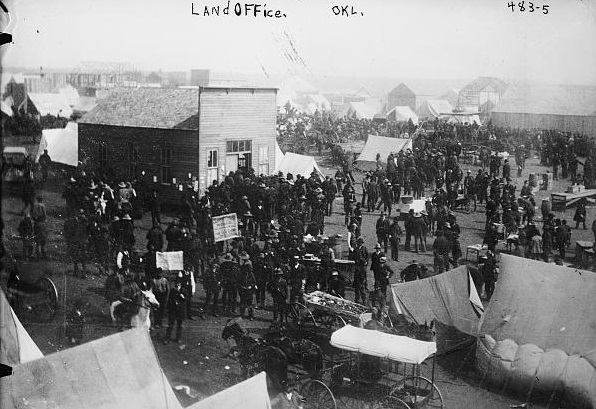

Land Office by Bain News Service

One reporter for Harper’s Weekly wrote, “Unlike Rome, the city of Guthrie was built in a day.” Oklahoma City soon boasted 10,000 inhabitants, “53 physicians, 97 lawyers, 47 barbers, 28 surveyors, 29 real estate agents, and 11 dentists.”

First blacksmith shop in Guthrie 1889

Guthrie A town ten days old

Looking for a town lot 1889

Oklahoma City, April 26, 1889

For the American Indians of the Five Civilized Tribes – who were relocated thought they had a permanent home in Oklahoma – that same night must have been full of sadness, anger, and despair.

SOURCE

- National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior

- Library of Congress

- The brief film is a clip from the 1936 documentary, The Plow that broke the Plain which depicts the Cherokee Land Rush. The documentary shows what happened to the Great Plains region of the United States and Canada when uncontrolled agricultural farming led to the Dust Bowl. It was written and directed by Pare Lorentz. The film was narrated by the American actor and baritone Thomas Hardie Chalmers.

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Banished: Lost & Forgotten Stories

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 marks a dark time in American history regarding the new country’s relationship with the Native American population. The Act called for the “voluntary or forcible removal of all Indians” residing in the eastern United States to the west of the Mississippi River. Between 1831 and 1837, approximately 46,000 Native Americans were forced to leave their homes in southeastern states.

ALABAMA FOOTPRINTS Banished reveals true stories, documents and news articles from this sad time in Alabama’s history. Some stories include:

Choctaw & Treaty Of Dancing Rabbit Creek

Private Contracts For Removal

Stockades In Alabama

The Long Trail West

Reverend Daniel S. Burtrick’s 1838 Journal

An Observer Writes His Memories