Can you believe that turpentine was once a booming industry all over the world? Turpentine is a fluid obtained by the distillation of resin from live trees, mainly pines. The many uses for turpentine expanded through accident and experiment until it practically dominated the burgeoning industry of America.

In the great pine forests of the South – gathering crude turpentine – North Carolina

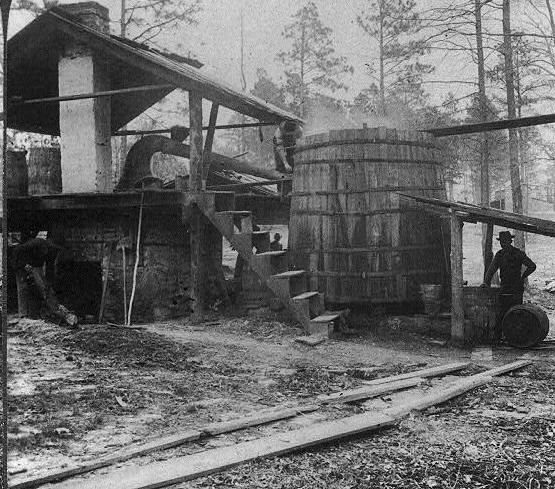

Distilling turpentine from the crude resin in the pine forests of North Carolina 1903

A hard, sticky amber rosin, sometimes called pitch, was made from the trees’ turpentine gum, or oleoresin. It was used to preserve ropes and rigging on sailing ships and to caulk the seams between timbers in the ships’ hulls.

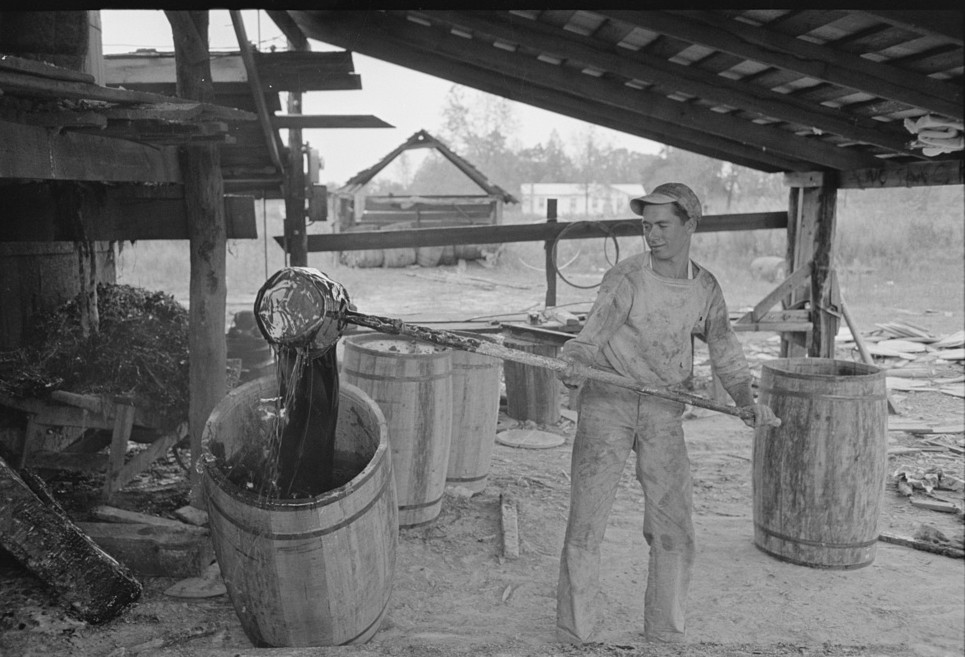

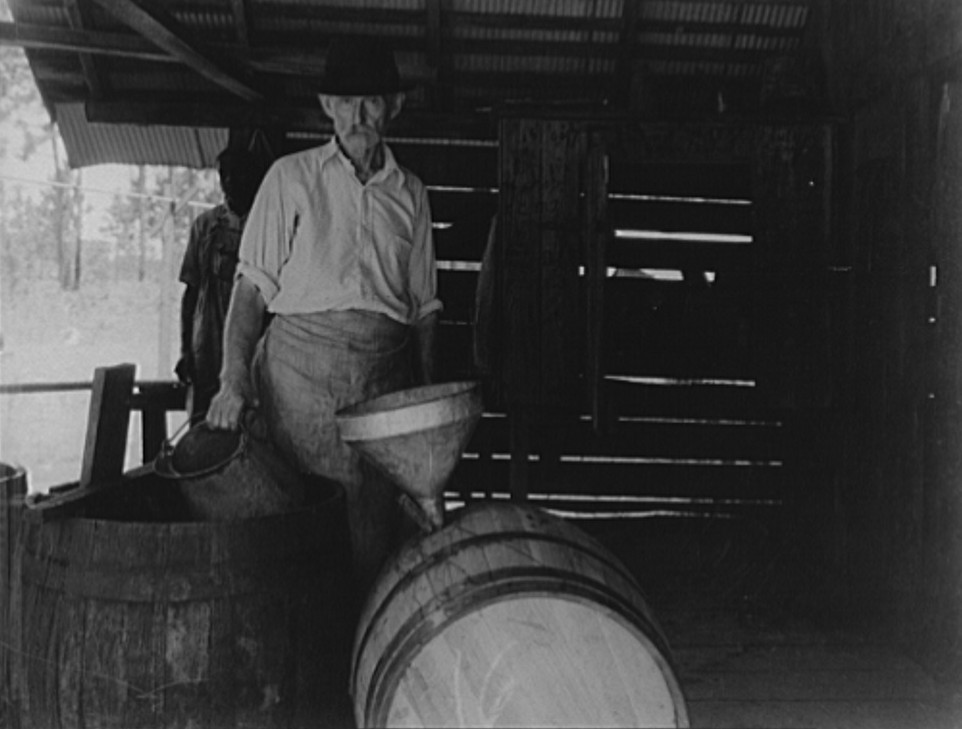

Workers at a Georgia Turpentine Still – July 1937 by Dorothea Lange

Tar kept ropes and sail rigging from decaying, and pitch on a boat’s sides and bottom prevented leaking. For this reason, turpentine products were called ‘naval stores’.

The collection of turpentine started during the Colonial Era. During this time England needed turpentine to free itself from foreign trade, and England’s colonies provided this necessary material.

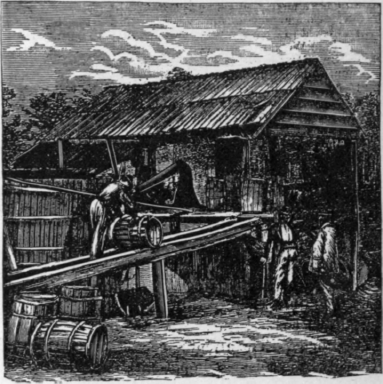

Pine tree girdled with two boxes in southern Georgia, near Valdosta June 1936 by Carl Mydans

In 1720, the English Parliament enacted a bounty to encourage colonists to engage in the industry, because Great Britain’s dependence on its naval trade necessitated many boats. In the 1720s and 1730s, the industry in the Northeast Cape Fear region of present-day Duplin County attracted Welsh migrants from Pennsylvania and Delaware.

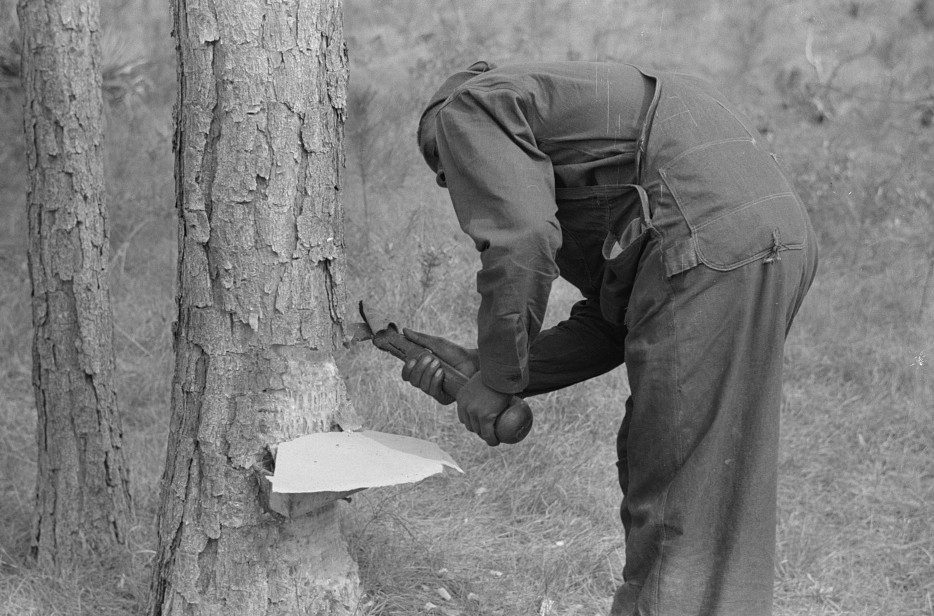

A hack used in chipping turpentine in a turpentine grove near Pembroke, Georgia Apr 1941 by Jack DeLano

By the 1770s, the production of naval stores was widespread in Eastern North Carolina, as noted by Janet Schaw, a well-educated Scot who toured the Cape Fear region a couple years prior to the American Revolution.

Turpentine farm, Clinton, N.C. 1909

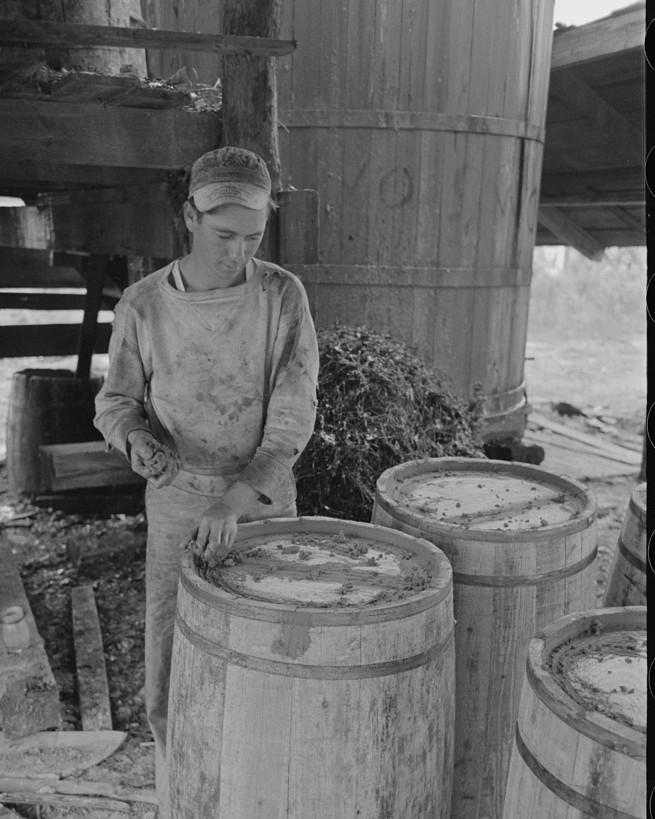

Terry Smith, one of the farmers living at Hazlehurst Farms. He was chipping turpentine at the farms to earn a livelihood. Hazlehurst, Georgia Apr 1941 by Jack Delano

Small farmers and their slaves (typically one to four on each farm) provided the infrastructure of the naval stores industry while growing grains and raising cattle.

Distilling Turpentine in 1903 North Carolina

Longleaf pines were destroyed by the technology of the day—scoring trees to cause them to “bleed” eventually killed them. A heavily tapped forest could be depleted and destroyed in a decade. When that happened the industry was forced to move on to find new forests to exploit.

Turpentine trees Florida 1936 by Dorothea Lange

After ships were made of steel and had engines, rosin was used in the manufacture of soap and other products and to wax bowstrings for musical instruments. Spirits of turpentine, which was separated from the pitch in stills, was – and still is – used as a paint thinner and solvent.

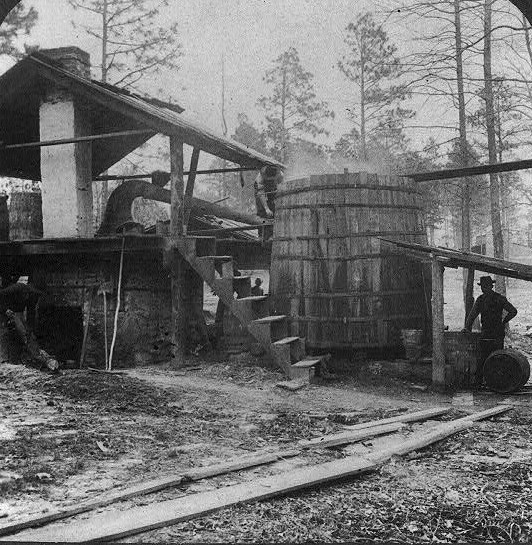

Older Type Turpentine Distillery

During the colonial period, turpentine was used mainly as a laxative or as a water repellent for cloth and leather, but demand for it increased exponentially during the nineteenth century.

Although soap manufacturers started using leftover resin from the stills in which turpentine had been extracted, turpentine was used primarily from 1800 to 1860 as an illuminant; the substance when combined with alcohol provided a cheap form of lighting that was used in homes, public buildings, and streets. This mixture was known as camphene, Teveline, or palmetto oil. By 1860, a less costly illuminant replaced the turpentine-based one: kerosene.

Florida Turpentine camp 1939 by Marion Post Walcott

Extracting turpentine from pine trees and processing it in backwoods stills was once Florida’s second-largest industry – after citrus – before the turn of the century. But it exacted a price on people and the environment unlike any other business.

Baker, Florida. The turpentine forests are about gone, but this mill on the edge of Baker still distills the gum June 1942 by John Collier

The work was hard for crews that chipped chevron-shaped gashes into pine trees, inserted metal sleeves and hung pots on them to catch the sap when it ran from early spring through October.

Chipping turpentine on a second-year face with a hack. Near Pembroke, Georgia 1941 Jack Delano

Turpentine chipper and slashed tree near Homerville, Georgia July 1937 by Dorothea Lange

Pulling operation of a four-year face in a turpentine grove near Pembroke, Georgia 1941 Jack DeLano

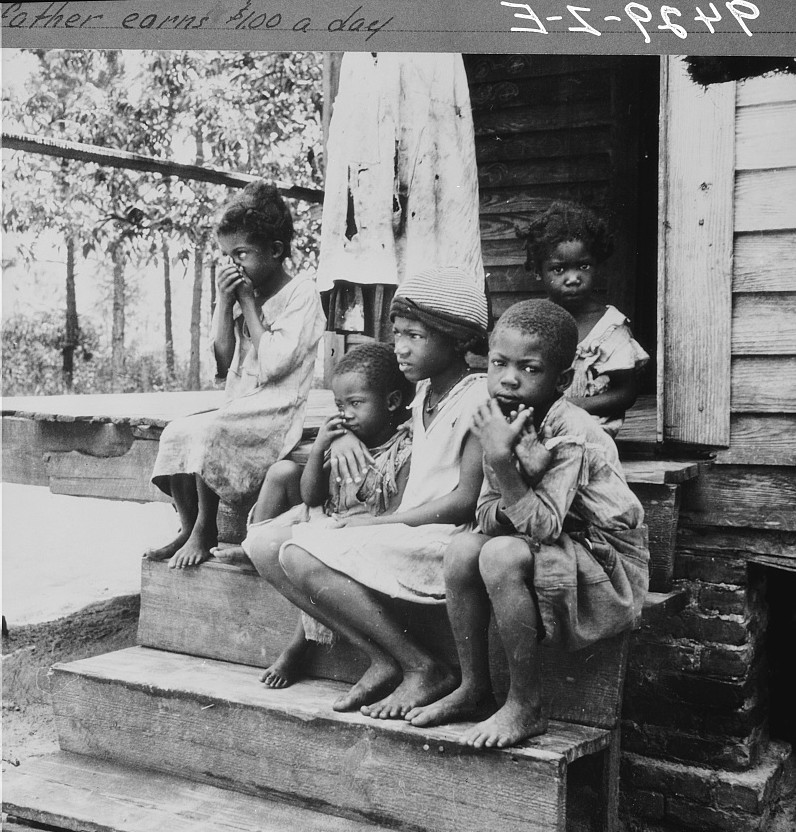

In addition, they were poorly paid – as little as $1 per day even in this century – and often were forced to buy food and supplies from the company store at inflated prices.

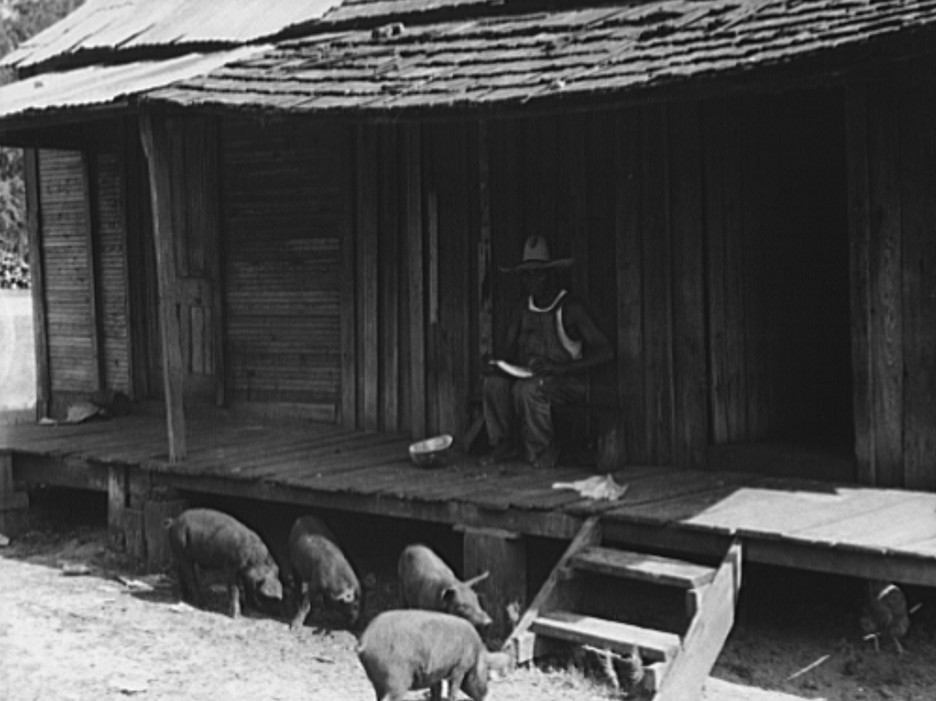

Home of turpentine workers near Godwinsville, Georgia July 1937 by Dorothea Lange

Georgia Turpentine workers home July 1937 by Dorothea Lange

After sapping much of Virginia’s forests, the industry moved south into the Carolinas (where slaves trampling through spilled pitch gave North Carolina its nickname, the ”Tar Heel” state) and then to Georgia, Burnett wrote in Florida’s Past: People and Events that Shaped the State, a collection of his columns from Florida Trend magazine.

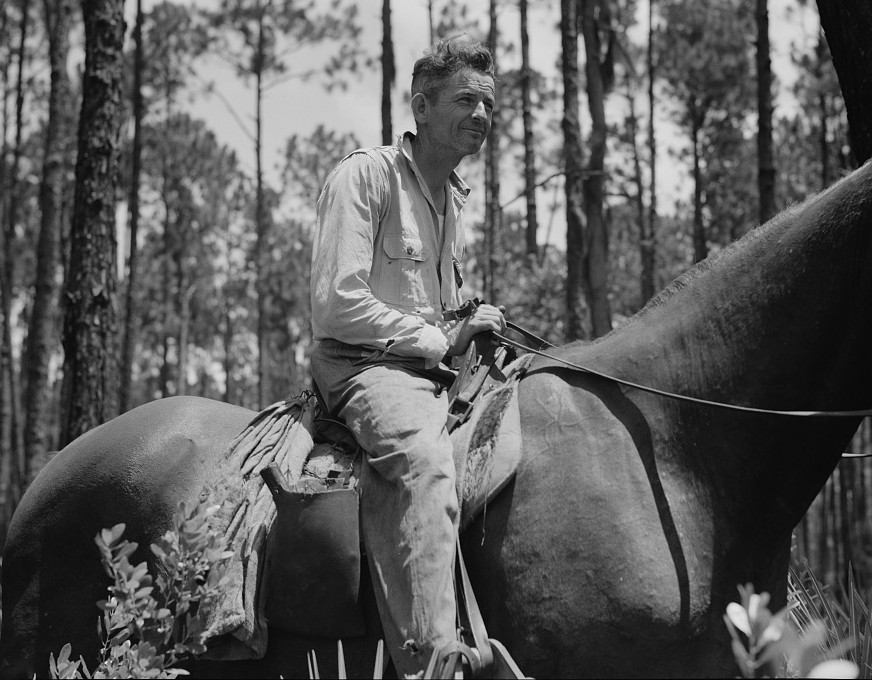

Overseer in the turpentine woods. Georgia July 1937 by Dorothea Lange

Many men, some with their families, followed the industry to Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas—everywhere the longleaf pine grew.

Children of turpentine worker near Cordele, Alabama. The father earns one dollar a day July 1936 Dorothea Lange

Late in the 19th century, Georgia’s forests were becoming depleted, and turpentine operators moved into Florida. There were small turpentine camps in Orange County as far back as the 1850s, but the industry took off after the Civil War.

Moving day in the turpentine pine forest country. Northern Florida July 1936 by Dorothea Lang

North Florida Turpentine Camp Jan 1939 by Marion Post Walcott

Blacks provided most of the labor at many camps and for many workers, conditions were little, if any, better than what their parents had experienced as slaves.

Wife of turpentine worker near DuPont, Georgia July 1937 by Dorothea Lange

Living conditions were primitive and harsh. Workers were crowded into shanties, given poor food and were forced to trade the scrip they earned for living necessities at above-market prices at the company store.

Valdosta, Georgia Turpentine workers home July 1937 by Dorothea Lange

If a worker tried to leave the camp, he could be arrested and brought back if he owed the store. Burnett wrote. The law rarely intervened at a turpentine camp unless someone was killed.

Waycross Georgia Turpentine dipper July 1937 by Dorothea Lange

Another view of the industry comes from George Clanton, whose father brought the family to east Orange County, Florida in the 1930s to run turpentine camps on Taylor and Gem creeks.

Georgia Turpentine worker July 1937 by Dorothea Lange

Clanton, interviewed in 1989 by Gertrude M. Gross for the Orange County Historical Society, said hundreds of workers his father brought here from Louisiana were grateful for jobs that let them escape unemployment in the Great Depression.

Worker at turpentine still caulking barrels for resin, State Line, Mississippi 1938 by Lee Russell

Workers were provided small houses at the camps free of charge and allowed to cultivate garden plots, he told Gross.

State Line, Mississippi Turpentine still Nov. 1938 by Russell Lee

In the 1930s, large distillation plants began to replace the 1,300 backwoods fire stills.

Abandoned turpentine still might be put to use by Hazlehurst Farms Inc., Hazlehurst, Georgia Apr. 1941 by Jack Delano

The exploitation of the long-leaf pine forest of the Deep South . . . was one means by which southerners recouped their capital after the war. . . . In approximately two generations, from 1870 to 1930, most of the original stands of long-leaf pine, covering 130,000,000 acres, were consumed. (Percival Perry in the Encyclopedia of Southern Culture)

Filtering hot rosin through sieves at a turpentine works in Statesboro, Georgia Apr. 1941 Jack Delano

Cleaning turpentine cups in boiling water at a still near Pembroke, Georgia 1941 by Jack Delano

By 1970, the turpentine industry, in decline for decades, had all but vanished from many states. Pulp mills had taken over the industry by providing turpentine and other chemicals as byproducts of the paper manufacturing process.

Amazon.com – Read eBooks using the FREE Kindle Reading App on Most Devices

Try a trial Membership by clicking the link below. Join Amazon Prime – Watch Over 40,000 Movies & TV Shows Anytime – Start Free Trial Now

You can now give a gift of Amazon Prime = click this link to learn how – Shop Amazon – Give the Gift of Amazon Prime

VINEGAR OF THE FOUR THIEVES: Recipes & curious tips from the past

Check out genealogy books and novels by Donna R. Causey